THE FOUNDATION

Alix Rosoit and Arnould IV Oudenaarde are prominent figures in the 13th century and they leave important traces in the region: the hospital and the ramparts in Lessines (there still is a tower along the Dender, near the hospital, while another tower and a walkway are visible behind the new post office), in Oudenaarde on the right bank of the Schelde, opposite St. Walburga, the small church Our Lady of Pamele, jewel of the transition from Romanesque to Gothic.

Lord Arnold IV, over 60 years of age in 1242, was probably hoping for a peaceful end to his life. The King Louis IX of France, at war against King Henry III of England, took advantage of the treaty of allegiance signed earlier by the Flemish lords to call for help. Arnold IV was thus forced to return to war despite his age. He took care to draw up his will and to include a provision in it on behalf of the poor: the rich and powerful were in the habit of providing for a substantial donation of money to be distributed to the poor on the day of their funeral, in the hope of redeeming their sins and entering paradise.

Wounded at the Battle of Taillebourg near Poitiers, in 1242, Arnold died a few weeks later. His wife Alice, inheriting a considerable fortune, would undertake to fulfil her husband’s last wishes. Rather than distributing the money, she probably had the idea of “investing” in founding a hospital for the poor.

THE HOSPITAL MOUVEMENT

The hospital of Lessines is contemporary of the whole hospital movement which developed in Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries. As a matter of fact, many hospitals were created, at the end of the 12th century, in the earldoms of Flandres and Hainaut. The St. John’s Hospital in Bruges, founded around 1180, was one of the first, one of the most famous and one of the best preserved. The hospitals of St. John of Damme, the Hospice Comtesse of Lille, Our Lady of the Bijloke in Ghent, the hospitals of Tournai and Brussels etc. are also worth mentioning. The Hospices of Beaune were founded only much later, in the middle of 15th century.

These hospitals were intended to accommodate the poor indigent patients, the needy of society. At the time, populations in the towns, sheltered within the circle of ramparts, were experiencing substantial demographic growth. Yet there was no form of social security, the small craftsmen of tradespeople who got sick very quickly lost their livelihoods and risked being left on the street, forced to beg to survive.

This social situation soon posed problems for the city governors who attempted to solve the problem by creating hospitals. Those institutions received whoever was unable to pay for “private medicine” at home, reserved for nobility and middle classes.

Our hospital therefore emerged in a period when Lessines was triving, having experienced a certain amount of development since the 12th century. The cloth industry was booming and trade was expanding owing to the building of a convered market and especially on account of the Dendre, the river which flows under the hospital and which enables cloth and other products to be transported abroad.

Nonetheless, that development and the increase in population in Lessines were going to foster the outbreak of diseases and epidemics. Since the leper quarters and the Beguine convent were insufficient to cater for the needs or the poor, it became necessary to open a hospital shelter.

The oldest document in the hospital records is a charter (June 1243) of John d’Oudenaarde (son of Alix and Arnould) allocationg 100 pounds of annual income to the hospital, a considerable amount to be taken from the estates of Maubeuge an Feignies belonging to Alix. The institution of the hospital is certanly prior to that.

THE COMMUNITY

As in many hospitals, the religious community of Lessines follows the rule of St. Augustine. This rule, flexible and well adapted to the hospitable life, insists mainly on the principle of charity, but also on obedience to the bishop. It is Guy de Laon, at the head of the bishopric of Cambrai, which, in July 1247, gives the Hospital its first statutes. Then completed by Nicolas de Fontaines in 1261, these rules organized the entire spiritual and daily life of the community in a precise way: the meal schedule, the reception of the poor and sick, the dress code, the instruction of the novices, the possibilities of exits and the regulations of the faults and punishments.

If these women devoted a large part of their day to the care of the sick and therefore to very “temporal” tasks, the fact remains that they had a very rich spiritual life, as evidenced by many artistic works sometimes unusual in their iconography, but quite readable as long as they are contextualized.

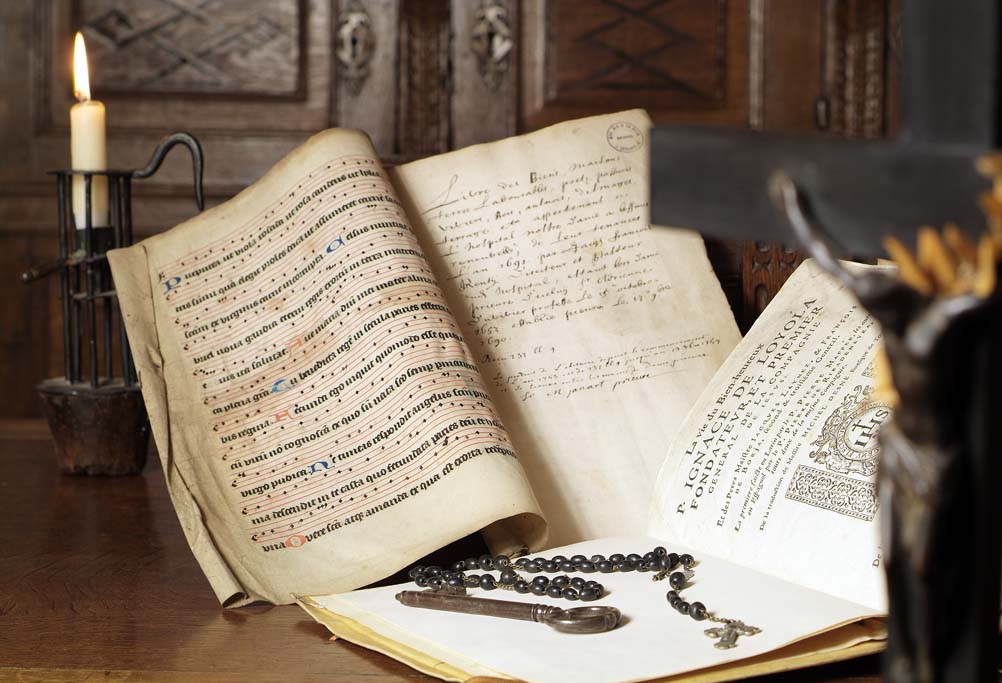

THE ARCHIVES

The Hospital Notre-Dame a la Rose of Lessines has an invaluable archive that dates back to its founding in the 13th century. It contains many important pieces: papal bulls, cartulas, rules and statutes of the institution, chirographs, charters, etc. Throughout its history, the hotel Dieu has produced numerous documents. Multiple account books, litigation files or patient records – which may seem prima facie less valuable – are inexhaustible sources of information on daily life in the heart of a hospital-based convent. These archives provide valuable information concerning, in particular, the land properties of the hospital, certain phases of construction and expansion of the site and the nuns who took care of the poor patients. Although historians have already looked at pieces of this collection and found some very interesting studies, it is certain that these archives have not yet revealed all their secrets.

In addition to the archives, the Sisters’ Library provides a better understanding of the lives of the Hospital nuns and the spiritual and literary influences that marked this community. We must not be mistaken, reading was not the prerogative of all. The books were the property of the convent and, before the teaching became general, only the nuns and priests were able to use them. The oldest works date back to the 16th century and the most recent ones were published in the second half of the 20th century. Most of these books are of a religious nature and are written in Latin or French. Although it is a hospital community, only a limited number of books on medical or medicinal topics are kept. Indeed, during the Ancien Regime, the sisters practiced only very limited medical gestures and their knowledge of this art was mainly derived from the experience gained within the community. “Bookish” knowledge counted for very little.

Annonce Importante / Belangrijke Mededeling

Annonce Importante / Belangrijke Mededeling